alexsidles

Paddler

[Cross-posted at alexsidles.com]

After an unsuccessful search in May, I returned in July to try again to find a minke whale. This time, I succeeded, to the tune of no less than four minke whales.

According to biologist Ellie Dorsey, July through September is the peak month for minke whales in our waters. The minkes’ favorite foraging habitat is the two shoals south of Cattle Point on San Juan Island: Salmon Bank, two miles offshore, and Hein Bank, nine miles offshore.

As I had in May, I launched at Otis Perkins County Day Park on Lopez Island and rode the morning ebb south to the banks. This time, however, I did not stop at Salmon Bank. I continued all the way to Hein Bank.

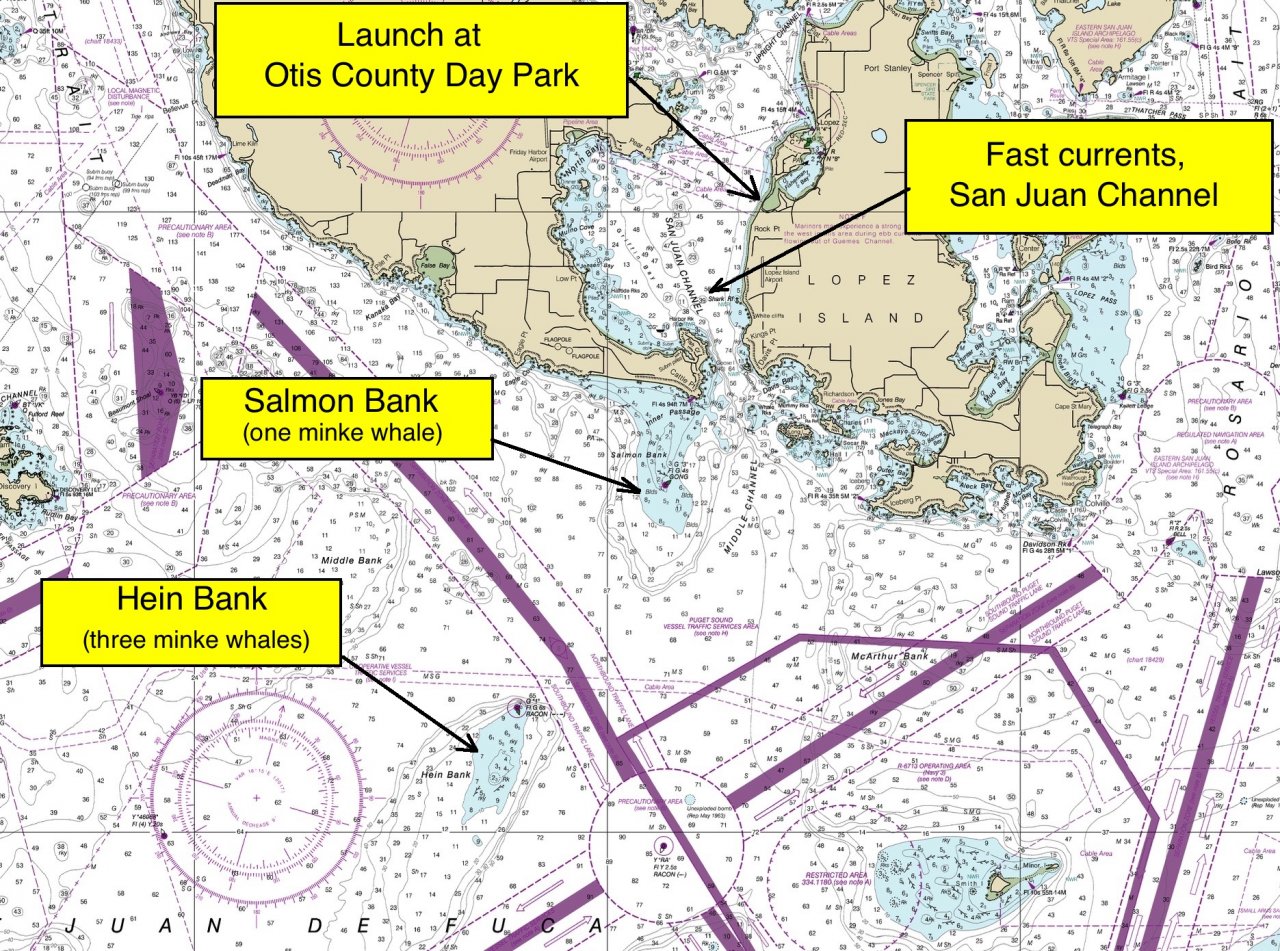

00 Route map. Maximum currents run above five knots in San Juan Channel.

At Otis County Day Park, shorebirds were foraging on both the muddy Fisherman Bay side and the rocky San Juan Channel side: western sandpipers, greater yellowlegs, and a killdeer.

When I launched early in the morning, advection fog was so thick I couldn’t see one side of San Juan Channel from the other. Above the low-lying fog, the sky was clear and the sun was shining. Occasionally, the bright sunlight created white rainbows, or “fog bows.”

01 Western sandpipers at launch point in Fisherman Bay. These are on their way south from the Arctic, having bred earlier in the summer.

02 Killdeer on launch beach, Otis Perkins County Day Park. Killdeers can be surprisingly hard to spot when they are blending in on pebbly beaches.

03 Looking north up San Juan Channel. The San Juans are one of the most beautiful parts of Washington.

04 White rainbow, San Juan Channel. The fog was so thick a passing sailboat stopped to ask me where I was going and whether I had a GPS.

Thanks to the fast, southward-ebbing current, I reached the Salmon Bank buoy just 45 minutes after launch. Visibility was less than a mile through the fog, but Salmon Bank is less than a mile across, so I figured I’d have a good chance to spot any minkes that might be present.

Great numbers of seabirds were present, including rhinoceros auklets, glaucous-winged and California gulls, and pelagic cormorants. A handful of common murres, pigeon guillemots, and Heerman’s gulls were also mixed in. All this was a good sign that baitfish were in the water, which would tend to attract minkes, but after half an hour’s drifting in the fog, I had not heard a single whale’s breath. I did, however, find a red-necked phalarope, a delicate little bird that nonetheless undertakes long, difficult marine migrations.

Determined not to suffer another miss of the whales, I set out for Hein Bank, seven miles farther out in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The fog cleared as I paddled, and soon I was enjoying a clear, sunny day, and mercifully calm: perfect summer weather for a long paddle.

At the Hein Bank buoy, I started hearing the deep exhalations of a whale. Try as I might, however, I was not able to spot it.

05 Kayaking across the Strait of Juan de Fuca toward Hein Bank. The Olympics are the most attractive of our state’s mountain ranges.

06 Pelagic cormorants atop Hein Bank buoy. The white structure behind them is the buoy’s radar beacon, or “racon.”

Most whale species breathe in sets. They take two to four breaths in short succession, all in the same approximate location, followed by a long dive during which they relocate. If you hear a whale’s first breath in the set or see its first spout, you can usually spot the whale when it comes up for the next breath in the set.

A minke whale, however, takes just a single breath and then disappears. Five to fifteen minutes later, it pops up again without warning, often far from its original location. It takes another single breath, then disappears again. Each time the whale breathes, it is only on the surface for approximately two seconds. There is no visible spout.

After forty-five minutes’ loitering at the Hein Bank buoy, I had only heard three breaths and had not seen any dorsal fins. I moved a mile farther south into the main part of Hein Bank, but I was starting to lose hope. There were so many recreational fishing boats it was hard to distinguish the breaths above all the engine noise. It seemed possible I might only be hearing harbor porpoises. The breaths sounded deeper and more prolonged than porpoise breaths, but that kind of thing can be difficult to judge, especially in a noisy environment. What must all this noise sound like to the sensitive ears of cetaceans?

Then, at about a quarter mile’s distance, I saw the unmistakable curved fin of a surfacing minke whale. It looked like the combination of a humpback whale’s arched body and the sweptback fin of a female orca.

In the main part of Hein Bank, there were two foraging minkes. They popped up every few minutes at various distances on either side of my boat. Sometimes, they came within fifty yards—so close I would bang my paddle against my hull to alert them not to collide with me.

Knowing in advance that minke whales would be difficult to photograph, I had rented a telephoto lens from a local camera shop. I expected my cheap little 55–200mm kit lens would lack the magnification to capture unpredictable minke whales, so I brought something with a little more reach.

07 The Nikon 400mm f2.8E FL ED AF-S VR. At all costs, do not drop this uninsured, $11,000 USD lens into the water.

Unfortunately, a 400mm telephoto was too much lens for a sea kayak. It was too long and too fragile to lay on deck. It certainly didn’t fit into the day hatch. I had to set it between my knees in the cockpit, with its nose tucked into a forty-liter drybag to protect it from bilgewater. In such a position, it was too cumbersome to access quickly.

Even when I did have it out, the lens and camera were too heavy to use for minke whales. At a combined weight of almost ten pounds (4.5 kg), I could heft the camera for a minute or two, but I could not hold it in the ready position for ten or fifteen minutes, waiting for a minke to surface. I had to set it down, between my knees, in the drybag, from which position it was impossible to raise it, aim it, and focus it during the two seconds each minke would remain on the surface.

Hoisting the camera also caused chaos with my other equipment on deck. On one occasion, a whale came up nearby, and I swung the camera up so quickly the lens knocked into my paddle, which knocked into my binoculars, which fell into the water and sank. The lens was so large I did not even notice the missing binoculars until afterward.

Finally, I could not hold the lens steady enough to take advantage of its powerful magnification. The sharpness of the shots from the 400mm was similar to that of enlarged shots from my kit lens, which took away the whole point of using a monster lens.

In the end, even though I observed more than thirty surfacings of minke whales (and heard three times that number), I was only able to take two photos, both of laughably bad quality. I’d have done much better to use my 55–200mm kit lens, despite its narrow aperture and low magnification, because I would at least have been able to hold it at the ready and aim it quickly as soon as a whale appeared.

08 Minke whale at Hein Bank. Or what you will.

09 Minke whale dorsal fin at Hein Bank.

Having worked so hard to find these whales, I took my time enjoying their company. Even though they are baleen whales, these minkes moved with the purposeful, predatory demeanor of orcas, not the ponderous roll of humpbacks or grays.

Eventually, the tide turned. The current began flowing north, and I must go with it. Moreover, the changing tide turned Hein Bank lumpy with short waves moving in opposing directions—not a pleasant environment for drifting.

On my way back north, I found a third minke in the vicinity of the Hein Bank buoy. This must have been the same individual I spent half an hour searching for unsuccessfully, but now it surfaced twice in just five minutes as I departed, giving me fantastic looks at its smooth, shiny flanks.

A professional whale-watching outfit also reported three minkes at Hein Bank the same day I was there, so I am confident of my whale count.

When I passed Salmon Bank, a fourth minke appeared. This one had a lovely brownish cast to its flanks. At one point, it surfaced so close I could see its blowhole.

In the mouth of San Juan Channel, the flood hit four and a half knots. A tide race two miles formed on either side of the channel, with a “vee” in the middle like the world’s largest river rapid. I kept clear of the bumpiest sections and flew the last four miles back to the parking lot in less than forty-five minutes.

10 Crossing Salmon Bank, heading toward San Juan Channel. Grassy San Juan Island on the left, forested Lopez Island on the right, mountainous Orcas Island in the background.

Even with meticulous planning, my hunts for marine mammals only succeed half the time. Such beautiful, inspiring animals are worth any amount of effort. Best of all, you don’t need expensive equipment to enjoy them. On the contrary, the less you bring, the better.

Alex

[Cross-posted at alexsidles.com]

After an unsuccessful search in May, I returned in July to try again to find a minke whale. This time, I succeeded, to the tune of no less than four minke whales.

According to biologist Ellie Dorsey, July through September is the peak month for minke whales in our waters. The minkes’ favorite foraging habitat is the two shoals south of Cattle Point on San Juan Island: Salmon Bank, two miles offshore, and Hein Bank, nine miles offshore.

As I had in May, I launched at Otis Perkins County Day Park on Lopez Island and rode the morning ebb south to the banks. This time, however, I did not stop at Salmon Bank. I continued all the way to Hein Bank.

00 Route map. Maximum currents run above five knots in San Juan Channel.

At Otis County Day Park, shorebirds were foraging on both the muddy Fisherman Bay side and the rocky San Juan Channel side: western sandpipers, greater yellowlegs, and a killdeer.

When I launched early in the morning, advection fog was so thick I couldn’t see one side of San Juan Channel from the other. Above the low-lying fog, the sky was clear and the sun was shining. Occasionally, the bright sunlight created white rainbows, or “fog bows.”

01 Western sandpipers at launch point in Fisherman Bay. These are on their way south from the Arctic, having bred earlier in the summer.

02 Killdeer on launch beach, Otis Perkins County Day Park. Killdeers can be surprisingly hard to spot when they are blending in on pebbly beaches.

03 Looking north up San Juan Channel. The San Juans are one of the most beautiful parts of Washington.

04 White rainbow, San Juan Channel. The fog was so thick a passing sailboat stopped to ask me where I was going and whether I had a GPS.

Thanks to the fast, southward-ebbing current, I reached the Salmon Bank buoy just 45 minutes after launch. Visibility was less than a mile through the fog, but Salmon Bank is less than a mile across, so I figured I’d have a good chance to spot any minkes that might be present.

Great numbers of seabirds were present, including rhinoceros auklets, glaucous-winged and California gulls, and pelagic cormorants. A handful of common murres, pigeon guillemots, and Heerman’s gulls were also mixed in. All this was a good sign that baitfish were in the water, which would tend to attract minkes, but after half an hour’s drifting in the fog, I had not heard a single whale’s breath. I did, however, find a red-necked phalarope, a delicate little bird that nonetheless undertakes long, difficult marine migrations.

Determined not to suffer another miss of the whales, I set out for Hein Bank, seven miles farther out in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The fog cleared as I paddled, and soon I was enjoying a clear, sunny day, and mercifully calm: perfect summer weather for a long paddle.

At the Hein Bank buoy, I started hearing the deep exhalations of a whale. Try as I might, however, I was not able to spot it.

05 Kayaking across the Strait of Juan de Fuca toward Hein Bank. The Olympics are the most attractive of our state’s mountain ranges.

06 Pelagic cormorants atop Hein Bank buoy. The white structure behind them is the buoy’s radar beacon, or “racon.”

Most whale species breathe in sets. They take two to four breaths in short succession, all in the same approximate location, followed by a long dive during which they relocate. If you hear a whale’s first breath in the set or see its first spout, you can usually spot the whale when it comes up for the next breath in the set.

A minke whale, however, takes just a single breath and then disappears. Five to fifteen minutes later, it pops up again without warning, often far from its original location. It takes another single breath, then disappears again. Each time the whale breathes, it is only on the surface for approximately two seconds. There is no visible spout.

After forty-five minutes’ loitering at the Hein Bank buoy, I had only heard three breaths and had not seen any dorsal fins. I moved a mile farther south into the main part of Hein Bank, but I was starting to lose hope. There were so many recreational fishing boats it was hard to distinguish the breaths above all the engine noise. It seemed possible I might only be hearing harbor porpoises. The breaths sounded deeper and more prolonged than porpoise breaths, but that kind of thing can be difficult to judge, especially in a noisy environment. What must all this noise sound like to the sensitive ears of cetaceans?

Then, at about a quarter mile’s distance, I saw the unmistakable curved fin of a surfacing minke whale. It looked like the combination of a humpback whale’s arched body and the sweptback fin of a female orca.

In the main part of Hein Bank, there were two foraging minkes. They popped up every few minutes at various distances on either side of my boat. Sometimes, they came within fifty yards—so close I would bang my paddle against my hull to alert them not to collide with me.

Knowing in advance that minke whales would be difficult to photograph, I had rented a telephoto lens from a local camera shop. I expected my cheap little 55–200mm kit lens would lack the magnification to capture unpredictable minke whales, so I brought something with a little more reach.

07 The Nikon 400mm f2.8E FL ED AF-S VR. At all costs, do not drop this uninsured, $11,000 USD lens into the water.

Unfortunately, a 400mm telephoto was too much lens for a sea kayak. It was too long and too fragile to lay on deck. It certainly didn’t fit into the day hatch. I had to set it between my knees in the cockpit, with its nose tucked into a forty-liter drybag to protect it from bilgewater. In such a position, it was too cumbersome to access quickly.

Even when I did have it out, the lens and camera were too heavy to use for minke whales. At a combined weight of almost ten pounds (4.5 kg), I could heft the camera for a minute or two, but I could not hold it in the ready position for ten or fifteen minutes, waiting for a minke to surface. I had to set it down, between my knees, in the drybag, from which position it was impossible to raise it, aim it, and focus it during the two seconds each minke would remain on the surface.

Hoisting the camera also caused chaos with my other equipment on deck. On one occasion, a whale came up nearby, and I swung the camera up so quickly the lens knocked into my paddle, which knocked into my binoculars, which fell into the water and sank. The lens was so large I did not even notice the missing binoculars until afterward.

Finally, I could not hold the lens steady enough to take advantage of its powerful magnification. The sharpness of the shots from the 400mm was similar to that of enlarged shots from my kit lens, which took away the whole point of using a monster lens.

In the end, even though I observed more than thirty surfacings of minke whales (and heard three times that number), I was only able to take two photos, both of laughably bad quality. I’d have done much better to use my 55–200mm kit lens, despite its narrow aperture and low magnification, because I would at least have been able to hold it at the ready and aim it quickly as soon as a whale appeared.

08 Minke whale at Hein Bank. Or what you will.

09 Minke whale dorsal fin at Hein Bank.

Having worked so hard to find these whales, I took my time enjoying their company. Even though they are baleen whales, these minkes moved with the purposeful, predatory demeanor of orcas, not the ponderous roll of humpbacks or grays.

Eventually, the tide turned. The current began flowing north, and I must go with it. Moreover, the changing tide turned Hein Bank lumpy with short waves moving in opposing directions—not a pleasant environment for drifting.

On my way back north, I found a third minke in the vicinity of the Hein Bank buoy. This must have been the same individual I spent half an hour searching for unsuccessfully, but now it surfaced twice in just five minutes as I departed, giving me fantastic looks at its smooth, shiny flanks.

A professional whale-watching outfit also reported three minkes at Hein Bank the same day I was there, so I am confident of my whale count.

When I passed Salmon Bank, a fourth minke appeared. This one had a lovely brownish cast to its flanks. At one point, it surfaced so close I could see its blowhole.

In the mouth of San Juan Channel, the flood hit four and a half knots. A tide race two miles formed on either side of the channel, with a “vee” in the middle like the world’s largest river rapid. I kept clear of the bumpiest sections and flew the last four miles back to the parking lot in less than forty-five minutes.

10 Crossing Salmon Bank, heading toward San Juan Channel. Grassy San Juan Island on the left, forested Lopez Island on the right, mountainous Orcas Island in the background.

Even with meticulous planning, my hunts for marine mammals only succeed half the time. Such beautiful, inspiring animals are worth any amount of effort. Best of all, you don’t need expensive equipment to enjoy them. On the contrary, the less you bring, the better.

Alex

[Cross-posted at alexsidles.com]