alexsidles

Paddler

[Cross-posted at alexsidles.com]

Race Rocks is home to the northernmost breeding colony of elephant seals in the world. Elephant seals are the world’s largest pinniped. Adult male northern elephant seals top out at an astonishing 8,200 pounds (3,700 kg), although most weigh just half that. The seals spend most of their lives at sea, coming ashore only to mate, pup, and molt. The molt is staggered by age and gender, with adult bulls molting in June though August.

In 2018, I visited Smith and Minor Islands in Washington in hopes of finding tufted puffins, which I did, and giant, molting elephant seal bulls, which I did not. However, the elephant seal colony at Race Rocks is larger and more reliable than the one at Smith and Minor Islands. I had high hopes a visit to Race Rocks in June would yield an encounter with these enormous creatures.

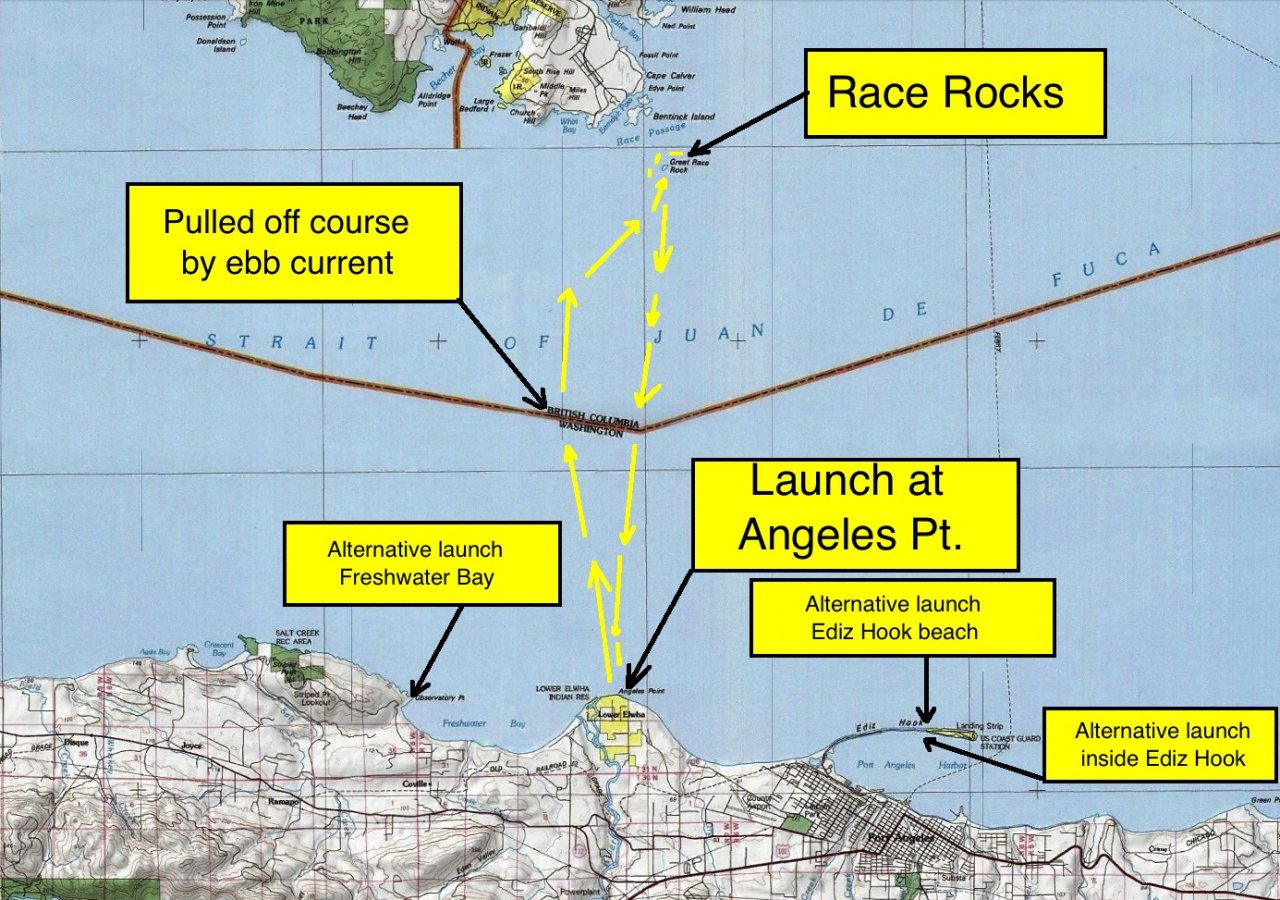

I launched from Angeles Point on the Washington side and paddled across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, circumnavigated Race Rocks twice, then returned across the strait to Angeles Point.

00 Route map. The beach at Angeles Point requires a quarter-mile carry down a gravel road to reach the beach.

Before I go on, let me present the most thrilling part of any trip report: legal analysis!

Didn’t Canada close its border with the US? Yes, but there are exceptions. Under Order in Council PC 2020-0469, § 6(d) (June 19, 2020), a boat may enter Canada from the US so long as the boat does not land, anchor, moor, or make contact with another boat in Canada, and so long as the boat returns to the US.

How did you clear customs when you entered Canada? No need. Under the Customs Act, RSC 1985, c. 1 (2nd Supp.), § 11(5)(a)(i), a boat that enters Canada from the US and departs Canada for the US without landing, anchoring, mooring, or making contact with another boat in Canada does not need to present itself to customs.

Could you have landed at Race Rocks? No. Landing at Race Rocks would have violated the Canadian border closure. Landing would also have required presentation to customs, the closest station of which is at Esquimault, nearly 11 miles (17 km) by kayak from Race Rocks. Finally, Race Rocks is an ecological reserve, so no one, American or Canadian, may land without permission, which I did not have.

How close could you get to Race Rocks? As close as I wanted, so long as I didn’t land. I must, however, obey the Marine Mammal Regulations, SOR/93-56, § 7(2), which prohibit disturbing any marine mammal, including causing it to move from its immediate vicinity, separating it from its group, and trapping it between a vessel and shore. More specific marine mammal regulations, such as numeric approach limits, apply to certain species listed in Schedule VI (including whales and killer whales), but seals are not listed in Schedule VI. In C. Gaz., vol. 146, no. 12, at 783–794, 784 (Mar. 24, 2012), DFO considered adopting a mandatory 100-meter approach limit for all marine mammals, but ultimately did not do so.

But aren’t the waters themselves a Marine Protected Area? No. According to DFO’s list of Marine Protected Areas, Race Rocks are only an “Area of Interest,” meaning a Marine Protected Area has been proposed but not adopted. Pearson College has been trying to get DFO to designate a Marine Protected Area since 1998, but DFO has not acted. Nor would Marine Protected Area status necessarily have precluded this trip. When DFO originally proposed (but did not adopt) Race Rocks Marine Protected Area regulations in C. Gaz., vol. 134, no. 44, at 3364–3372 (Oct. 28, 2000), the proposed regulations restricted fishing but not entry. In the absence of a Marine Protected Area, fishing at Race Rocks is subject to certain specific closures of commercial fishing and rockfish fishing, but not other types of fishing and not entry.

How did you clear US customs on your return? No need. Under the Tariff Act, 19 USC § 1433(a)(1), a vessel must present itself upon arrival from a “foreign port or place.” However, a boat that departs the US, enters foreign waters, and returns to the US without landing, anchoring, or mooring in a foreign country, and without receiving or unloading goods to another boat, has not arrived from a “foreign port or place.” See U.S. ex rel. Claussen v. Day, Comm’r of Immigration, 279 U.S. 398 (1929). According to US customs, such a boat has made a “cruise to nowhere” and does not require presentation. See Bimini Superfast Operations LLC v. Winkowski, 994 F.Supp.2d 106 (D.D.C. 2014).

But isn’t the US border closed? Yes, but there are exceptions. Under the Secretary of Homeland Security’s decision of June 24, 2020, 85 Fed. Reg. 37744, customs will not process non-essential entrants at land ports of entry, including recreational boaters. However, as noted above, a voyage to nowhere does not require presentation at any port of entry, much less a “land port of entry.” In addition, the decision provides that US persons returning to the US are “essential travellers” not subject to the closure.

So this crazy trip was legal? My crazy trip was legal. Your crazy trip may not be. I am not your attorney. I am not giving you legal advice. You should not act on the basis of anything you read here. Consult an immigration attorney.

Could a Canadian do the same trip in reverse? That’s not a safe assumption. A voyage originating in Canada is subject to different Canadian laws and different American laws than my trip was. Consult an immigration attorney.

Can we talk about kayaking now? I thought you’d never ask!

01 Kayaking at dawn, Strait of Juan de Fuca. Sunrise over the sea is a majestic, almost alien spectacle.

The Strait of Juan de Fuca is subject to a sometimes-vicious combination of wind, swell, and tidal current. In summer, onshore flow caused by static high-pressure systems over the ocean leads to westerly winds that routinely reach 30 knots. Ocean swells generate large, breaking waves on many of the launching beaches. Strong countercurrents form in the vicinity of Race Rocks, and tide races occur at many points within a few miles of shore.

Using DFO’s Current Atlas Juan de Fuca Strait to Strait of Georgia, I calculated what time I would need to depart the Washington coast to arrive at Race Rocks roughly during slack current. The answer varied depending on which launching point I used, which in turn depended on ocean swells—more sheltered launches tended to be farther from Race Rocks, requiring more time for the crossing. On Saturday, I visited several possible launch points to scout swells and eventually settled on a launch from Angeles Point, which would require a 5:00 AM launch time to reach Race Rocks at slack.

Kayaking across the Strait of Juan de Fuca toward Vancouver Island. Around twenty freighters of various sizes and descriptions crossed the strait during my trip, but none came closer than two miles.

The Straight of Juan de Fuca at dawn was a beautiful place to kayak. Once I was off the beach and through the tide races, everything went so quiet I could hear the wing beats of individual alcids as they went about their foraging. From time to time, schools of baitfish would ripple the surface of the water in their desperation to escape hunting salmon, who were so voracious they would sometimes hurl themselves out of the water and fall back with a splash.

Slow, eight-foot swells rolled in from my left and hoisted me up and down like escalators. Wind waves of such a height would be extremely dangerous, so at first, my instinct was to fear the swells would capsize me. But they never broke, and soon I came to enjoy the feeling of standing like a giant atop their crests, as if I myself had absorbed part of the ocean’s power.

I reached Race Rocks after two and a half hours’ paddling. There were harbor seals in the water but none on the rocks, so I was able to circumnavigate the main island at fifty meters’ distance, looking for elephant seals hauled out ashore to molt.

03 Approaching Race Rocks from south. From shore on the Washington side, the lighthouse was barely visit to the naked eye.

The tail end of a powerful ebb was still running during my crossing. The current pulled me rapidly out to sea, so much so that I had to set a sharp angle to avoid missing Race Rocks altogether.

A GPS was invaluable during this crossing, even after the lighthouse came into sight. The currents swirled so unpredictably, my course veered by thirty degrees every half hour or so. Heaven forbid a kayaker ever take any but the most direct course possible!

I had planned to arrive out of the southwest and circumnavigate Race Rocks counterclockwise, but the current switched to a flood that pushed me so far east I ended up arriving out of the south and circumnavigating clockwise.

04 Arriving at Race Rocks. As seems to be all but standard practice in the field, one of the former lighthouse keepers here has written a book about life on the island.

On the east side of the main island, I spotted a sea otter just outside the kelp line. This was the farthest inland I had ever encountered this species, although I had heard reports of a lone individual at Lopez Island, thirty miles farther down the strait.

Unfortunately, I did not find any elephant seals. Two adult males had been molting here since late May, but they were not present today—or if they were, they were in one of the rocky depressions in the center of the island, invisible to a kayaker sitting low on the water.

05 Sea otter at Race Rocks. It’s rare to encounter just one sea otter—usually, there is either a herd or none—but Race Rocks is near the limit of this species’s range, so perhaps this one has been unable to entice a mate.

06 Pigeon guillemots at Race Rocks. The jetty they are perched on is one of the places the elephant seals like to haul out, but no seals today.

There never was a proper slack current at Race Rocks. Instead, the current split around the island, forming a gentle counterclockwise gyre on the east side of the main island, but the current speed through the channels remained at least two knots. The current helped me circumnavigate the island twice, searching for elephant seals, but to no avail.

07 Race Rocks lighthouse. Staff from Pearson College man the island year-round to conduct scientific experiments and deter illegal activity, but staff did not appear to be present today.

08 Kayaking at Race Rocks. By late morning, it was warm enough I peeled off my drysuit and woolies and paddled back across the Strair of Juan de Fuca in a t-shirt.

On the way back across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the sun came out and the wind died down. Even the ocean swells abated until near the American coast, when they returned at full strength. In the warm, blue stillness, I heard a humpback whale’s gasping breath. I spun around in a circle until I spotted its flukes on its last dive of the set.

There were a lot of alcids in the strait, especially rhinoceros auklets and pigeon guillemots. All of the Big Four were present, but the best encounter came near the end of the crossing: a lone Cassin’s auklet swam in front of my boat not thirty meters distant. This is a species that normally forages over the continental shelf, so kayakers rarely encounter it. However, a small number are known to frequent the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and I was lucky to meet one.

09 Rhinoceros auklets, Strait of Juan de Fuca. This species’s primary Washington nesting site is at Protection Island, just thirty miles away, so it was no surprise to see so many.

10 Cassin’s auklet, Strait of Juan de Fuca. This is our most numerous alcid but also the hardest to find at sea.

11 Kayaking from BC across Strait of Juan de Fuca to Washington. The Olympic Peninsula is one of the most beautiful parts of the state.

When I reached Angeles Point, I was dismayed to find forty surfers in the water at the exact stretch of beach I needed to come ashore. The gentle, six-inch wavelets that had greeted me at dawn had now swelled to three-foot breakers, which the local surfers were riding with great aplomb.

The swell height had not increased, so I can only surmise that the direction of the swell must have changed, or perhaps it had something to do with the tide. At any rate, I had no choice but to surf my way in.

I shot down the wave face like a torpedo, but eventually the whitewater overtook me, my boat broached, and my side-surfing lasted approximately one second before I capsized. By then, the wave had already carried me through the break into waist-deep water, so I simply waded ashore with my boat.

No day is a disappointment that includes a sea otter and a humpback whale. The Cassin’s auklet was another unexpected treat, doubly so since I had made an unsuccessful attempt to find them at one of their breeding islands in 2019.

As for the elephant seals, they gave me a beautiful voyage. Without them I would never have taken the road.

—Alex Sidles

[Cross-posted at alexsidles.com]

Race Rocks is home to the northernmost breeding colony of elephant seals in the world. Elephant seals are the world’s largest pinniped. Adult male northern elephant seals top out at an astonishing 8,200 pounds (3,700 kg), although most weigh just half that. The seals spend most of their lives at sea, coming ashore only to mate, pup, and molt. The molt is staggered by age and gender, with adult bulls molting in June though August.

In 2018, I visited Smith and Minor Islands in Washington in hopes of finding tufted puffins, which I did, and giant, molting elephant seal bulls, which I did not. However, the elephant seal colony at Race Rocks is larger and more reliable than the one at Smith and Minor Islands. I had high hopes a visit to Race Rocks in June would yield an encounter with these enormous creatures.

I launched from Angeles Point on the Washington side and paddled across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, circumnavigated Race Rocks twice, then returned across the strait to Angeles Point.

00 Route map. The beach at Angeles Point requires a quarter-mile carry down a gravel road to reach the beach.

Before I go on, let me present the most thrilling part of any trip report: legal analysis!

Didn’t Canada close its border with the US? Yes, but there are exceptions. Under Order in Council PC 2020-0469, § 6(d) (June 19, 2020), a boat may enter Canada from the US so long as the boat does not land, anchor, moor, or make contact with another boat in Canada, and so long as the boat returns to the US.

How did you clear customs when you entered Canada? No need. Under the Customs Act, RSC 1985, c. 1 (2nd Supp.), § 11(5)(a)(i), a boat that enters Canada from the US and departs Canada for the US without landing, anchoring, mooring, or making contact with another boat in Canada does not need to present itself to customs.

Could you have landed at Race Rocks? No. Landing at Race Rocks would have violated the Canadian border closure. Landing would also have required presentation to customs, the closest station of which is at Esquimault, nearly 11 miles (17 km) by kayak from Race Rocks. Finally, Race Rocks is an ecological reserve, so no one, American or Canadian, may land without permission, which I did not have.

How close could you get to Race Rocks? As close as I wanted, so long as I didn’t land. I must, however, obey the Marine Mammal Regulations, SOR/93-56, § 7(2), which prohibit disturbing any marine mammal, including causing it to move from its immediate vicinity, separating it from its group, and trapping it between a vessel and shore. More specific marine mammal regulations, such as numeric approach limits, apply to certain species listed in Schedule VI (including whales and killer whales), but seals are not listed in Schedule VI. In C. Gaz., vol. 146, no. 12, at 783–794, 784 (Mar. 24, 2012), DFO considered adopting a mandatory 100-meter approach limit for all marine mammals, but ultimately did not do so.

But aren’t the waters themselves a Marine Protected Area? No. According to DFO’s list of Marine Protected Areas, Race Rocks are only an “Area of Interest,” meaning a Marine Protected Area has been proposed but not adopted. Pearson College has been trying to get DFO to designate a Marine Protected Area since 1998, but DFO has not acted. Nor would Marine Protected Area status necessarily have precluded this trip. When DFO originally proposed (but did not adopt) Race Rocks Marine Protected Area regulations in C. Gaz., vol. 134, no. 44, at 3364–3372 (Oct. 28, 2000), the proposed regulations restricted fishing but not entry. In the absence of a Marine Protected Area, fishing at Race Rocks is subject to certain specific closures of commercial fishing and rockfish fishing, but not other types of fishing and not entry.

How did you clear US customs on your return? No need. Under the Tariff Act, 19 USC § 1433(a)(1), a vessel must present itself upon arrival from a “foreign port or place.” However, a boat that departs the US, enters foreign waters, and returns to the US without landing, anchoring, or mooring in a foreign country, and without receiving or unloading goods to another boat, has not arrived from a “foreign port or place.” See U.S. ex rel. Claussen v. Day, Comm’r of Immigration, 279 U.S. 398 (1929). According to US customs, such a boat has made a “cruise to nowhere” and does not require presentation. See Bimini Superfast Operations LLC v. Winkowski, 994 F.Supp.2d 106 (D.D.C. 2014).

But isn’t the US border closed? Yes, but there are exceptions. Under the Secretary of Homeland Security’s decision of June 24, 2020, 85 Fed. Reg. 37744, customs will not process non-essential entrants at land ports of entry, including recreational boaters. However, as noted above, a voyage to nowhere does not require presentation at any port of entry, much less a “land port of entry.” In addition, the decision provides that US persons returning to the US are “essential travellers” not subject to the closure.

So this crazy trip was legal? My crazy trip was legal. Your crazy trip may not be. I am not your attorney. I am not giving you legal advice. You should not act on the basis of anything you read here. Consult an immigration attorney.

Could a Canadian do the same trip in reverse? That’s not a safe assumption. A voyage originating in Canada is subject to different Canadian laws and different American laws than my trip was. Consult an immigration attorney.

Can we talk about kayaking now? I thought you’d never ask!

01 Kayaking at dawn, Strait of Juan de Fuca. Sunrise over the sea is a majestic, almost alien spectacle.

The Strait of Juan de Fuca is subject to a sometimes-vicious combination of wind, swell, and tidal current. In summer, onshore flow caused by static high-pressure systems over the ocean leads to westerly winds that routinely reach 30 knots. Ocean swells generate large, breaking waves on many of the launching beaches. Strong countercurrents form in the vicinity of Race Rocks, and tide races occur at many points within a few miles of shore.

Using DFO’s Current Atlas Juan de Fuca Strait to Strait of Georgia, I calculated what time I would need to depart the Washington coast to arrive at Race Rocks roughly during slack current. The answer varied depending on which launching point I used, which in turn depended on ocean swells—more sheltered launches tended to be farther from Race Rocks, requiring more time for the crossing. On Saturday, I visited several possible launch points to scout swells and eventually settled on a launch from Angeles Point, which would require a 5:00 AM launch time to reach Race Rocks at slack.

Kayaking across the Strait of Juan de Fuca toward Vancouver Island. Around twenty freighters of various sizes and descriptions crossed the strait during my trip, but none came closer than two miles.

The Straight of Juan de Fuca at dawn was a beautiful place to kayak. Once I was off the beach and through the tide races, everything went so quiet I could hear the wing beats of individual alcids as they went about their foraging. From time to time, schools of baitfish would ripple the surface of the water in their desperation to escape hunting salmon, who were so voracious they would sometimes hurl themselves out of the water and fall back with a splash.

Slow, eight-foot swells rolled in from my left and hoisted me up and down like escalators. Wind waves of such a height would be extremely dangerous, so at first, my instinct was to fear the swells would capsize me. But they never broke, and soon I came to enjoy the feeling of standing like a giant atop their crests, as if I myself had absorbed part of the ocean’s power.

I reached Race Rocks after two and a half hours’ paddling. There were harbor seals in the water but none on the rocks, so I was able to circumnavigate the main island at fifty meters’ distance, looking for elephant seals hauled out ashore to molt.

03 Approaching Race Rocks from south. From shore on the Washington side, the lighthouse was barely visit to the naked eye.

The tail end of a powerful ebb was still running during my crossing. The current pulled me rapidly out to sea, so much so that I had to set a sharp angle to avoid missing Race Rocks altogether.

A GPS was invaluable during this crossing, even after the lighthouse came into sight. The currents swirled so unpredictably, my course veered by thirty degrees every half hour or so. Heaven forbid a kayaker ever take any but the most direct course possible!

I had planned to arrive out of the southwest and circumnavigate Race Rocks counterclockwise, but the current switched to a flood that pushed me so far east I ended up arriving out of the south and circumnavigating clockwise.

04 Arriving at Race Rocks. As seems to be all but standard practice in the field, one of the former lighthouse keepers here has written a book about life on the island.

On the east side of the main island, I spotted a sea otter just outside the kelp line. This was the farthest inland I had ever encountered this species, although I had heard reports of a lone individual at Lopez Island, thirty miles farther down the strait.

Unfortunately, I did not find any elephant seals. Two adult males had been molting here since late May, but they were not present today—or if they were, they were in one of the rocky depressions in the center of the island, invisible to a kayaker sitting low on the water.

05 Sea otter at Race Rocks. It’s rare to encounter just one sea otter—usually, there is either a herd or none—but Race Rocks is near the limit of this species’s range, so perhaps this one has been unable to entice a mate.

06 Pigeon guillemots at Race Rocks. The jetty they are perched on is one of the places the elephant seals like to haul out, but no seals today.

There never was a proper slack current at Race Rocks. Instead, the current split around the island, forming a gentle counterclockwise gyre on the east side of the main island, but the current speed through the channels remained at least two knots. The current helped me circumnavigate the island twice, searching for elephant seals, but to no avail.

07 Race Rocks lighthouse. Staff from Pearson College man the island year-round to conduct scientific experiments and deter illegal activity, but staff did not appear to be present today.

08 Kayaking at Race Rocks. By late morning, it was warm enough I peeled off my drysuit and woolies and paddled back across the Strair of Juan de Fuca in a t-shirt.

On the way back across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the sun came out and the wind died down. Even the ocean swells abated until near the American coast, when they returned at full strength. In the warm, blue stillness, I heard a humpback whale’s gasping breath. I spun around in a circle until I spotted its flukes on its last dive of the set.

There were a lot of alcids in the strait, especially rhinoceros auklets and pigeon guillemots. All of the Big Four were present, but the best encounter came near the end of the crossing: a lone Cassin’s auklet swam in front of my boat not thirty meters distant. This is a species that normally forages over the continental shelf, so kayakers rarely encounter it. However, a small number are known to frequent the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and I was lucky to meet one.

09 Rhinoceros auklets, Strait of Juan de Fuca. This species’s primary Washington nesting site is at Protection Island, just thirty miles away, so it was no surprise to see so many.

10 Cassin’s auklet, Strait of Juan de Fuca. This is our most numerous alcid but also the hardest to find at sea.

11 Kayaking from BC across Strait of Juan de Fuca to Washington. The Olympic Peninsula is one of the most beautiful parts of the state.

When I reached Angeles Point, I was dismayed to find forty surfers in the water at the exact stretch of beach I needed to come ashore. The gentle, six-inch wavelets that had greeted me at dawn had now swelled to three-foot breakers, which the local surfers were riding with great aplomb.

The swell height had not increased, so I can only surmise that the direction of the swell must have changed, or perhaps it had something to do with the tide. At any rate, I had no choice but to surf my way in.

I shot down the wave face like a torpedo, but eventually the whitewater overtook me, my boat broached, and my side-surfing lasted approximately one second before I capsized. By then, the wave had already carried me through the break into waist-deep water, so I simply waded ashore with my boat.

No day is a disappointment that includes a sea otter and a humpback whale. The Cassin’s auklet was another unexpected treat, doubly so since I had made an unsuccessful attempt to find them at one of their breeding islands in 2019.

As for the elephant seals, they gave me a beautiful voyage. Without them I would never have taken the road.

—Alex Sidles

[Cross-posted at alexsidles.com]

Last edited: